File download is hosted on Megaupload

Fascism has never been absent from the US, but today it is enjoying a vogue that especially reminds me of the 1980’s and ’90’s when racist skinheads, white supremacists and militias gobbled up media attention, appearing on national TV shows like The Geraldo Rivera Show (where Rivera had his nose broken in an on-the-air brawl), in mainstream magazines like Rolling Stone and Time, and on the local and national news. Ronald Reagan was president then; a man who engaged in bellicose political rhetoric and who advocated trickle-down economic policies showing a lot of sympathy for the rich while shrugging off the concerns of the poor. At the time, it seemed as if we were in the midst of some sort of right-wing revolution taking place both in the streets and in the halls of government.

Today, it feels like the 1980’s all over again. In place of Reagan, we have Trump. In place of Geraldo Rivera, we now have countless internet websites, blogs, podcasts and cable TV stations that cater to the ready-made prejudices of audiences, promoting hysteria and factionalism. We still have racists and militias. And, just like in the 1980’s, we also have militant anti-fascists.

Antifa is a moniker used today that refers to a loose association of activists currently doing battle in the streets against groups of racists, alt-righters and self-avowed fascists. Antifa stands for “Anti-fascist,” and the one thing that unites this otherwise diverse group is a conviction that violence is a legitimate tool in the resistance against public congregations of militant right-wingers. Rejecting the tradition advocated by Ghandi and Martin Luther King, Jr., Antifa instead embraces the view that violence must be met with violence, and that in the battle against fascism any means necessary – including extreme brutality – must be used:

You fight them by writing letters and making phone calls so you don’t have to fight them with fists. You fight them with fists so you don’t have to fight them with knives. You fight them with knives so you don’t have to fight them with guns. You fight them with guns so you don’t have to fight them with tanks. (Murry, quote from the back cover of Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook)

Political liberals and conservatives alike detest the movement, as it rejects many of the taken for granted assumptions of polite, mainstream, liberal society. Most obviously, Antifa rejects the view that only government agencies have the legitimacy to use violence. Another principle rejected by Antifa is the belief that free speech is a sacred right. Lacking confidence in either the goodness or the competency of government, members advocate an anarchistic approach to justice, seeing it as the duty of individuals to take responsibility for monitoring and policing expressions of bigotry that occur in the streets. As it challenges the very assumptions upon which liberal democracies are founded, it is no wonder that democrats and republicans, liberals and conservatives, are united in their denunciations of Antifa.

Political liberals and conservatives alike detest the movement, as it rejects many of the taken for granted assumptions of polite, mainstream, liberal society. Most obviously, Antifa rejects the view that only government agencies have the legitimacy to use violence. Another principle rejected by Antifa is the belief that free speech is a sacred right. Lacking confidence in either the goodness or the competency of government, members advocate an anarchistic approach to justice, seeing it as the duty of individuals to take responsibility for monitoring and policing expressions of bigotry that occur in the streets. As it challenges the very assumptions upon which liberal democracies are founded, it is no wonder that democrats and republicans, liberals and conservatives, are united in their denunciations of Antifa.

There is very little reliable information about Antifa in the mainstream media, but I recently read two books that give interesting insider’s views of the anti-fascist movement, its history and its philosophy.

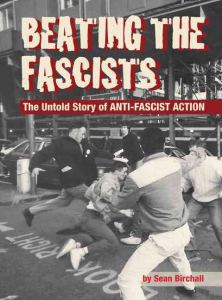

Sean Birchall’s Beating the Fascists is a massive, 400 page history of AFA (Anti-Fascist Action), a British precursor to the current Antifa movement. Spanning the years from 1977 through the 2000’s, the bulk of this book is devoted to accounts of street fights between anti- and pro-fascists.

Sean Birchall’s Beating the Fascists is a massive, 400 page history of AFA (Anti-Fascist Action), a British precursor to the current Antifa movement. Spanning the years from 1977 through the 2000’s, the bulk of this book is devoted to accounts of street fights between anti- and pro-fascists.

Birchall’s book reconstructs a mind-bending lineage of organizations that were involved in fighting not only fascists, but one another. I must confess that after reading it, I feel in some ways more confused than ever about the various allegiances and hostilities between the staggering number of leftist, anti-fascist organizations that existed during the 1980’s and 90’s. In addition to AFA, there was ANL (Anti-Nazi League), SWP (Socialist Worker’s Party), Red Action, ARA (Anti-Racist Action), CW (Class War), DAM (Direct Action Movement), and on and on. I still can’t keep them all straight in my head. The one thing that is clear is that AFA emerged due to disagreement among these various groups over the use of violence in the streets. After being condemned and marginalized by more moderate members of the left, AFA was launched in 1985 with the following “Statement of Aims”:

This conference sees the need to build an anti-fascist front of groups willing to combat fascist activity in this country. We need to oppose racism and fascism physically, on the streets, and ideologically. We support the right of ethnic minority groups and groups under threat to organize for their physical defence and see the need for us to organise in their support. This grouping should be organised on nonsectarian and democratic lines with equal representation for all groups involved. (p. 107)

The accounts of street fighting described in Birchall’s book are often thrilling. There is the battle between National Front skinheads and non-racist skinheads in Harrogate during an outdoor concert featuring the Redskins. There is the battle in Hyde Park when AFA decided to take a stand against the presence of Blood and Honor skinheads in the neighborhood. And there is the now famous “Battle of Waterloo” when AFA organized to shut down a concert by the White Power band Screwdriver. The picture that emerges from the first- and second-hand accounts of these street actions is of a surprisingly organized and committed group of militant anti-fascists, operating systematically and in concert with one another efficiently and effectively. This was more than just sporadic, random gang violence. It was part of an organized campaign leveled against the equally organized campaign of right-wing political forces in Britain struggling for control of the streets, neighborhoods and, ultimately, the government policies of the country. It was a ground-up movement, premised on the belief that if you can’t be safe in your own neighborhood, if you can’t control your own immediate environment, then you have no chance of being safe in your own country as a whole. I admire the commitment and the bravery of the individuals that Birchall interviews in his book; people willing, at a moment’s notice, to drop everything in order to physically confront bigotry in the streets so that it would not creep upwards into the halls of political power.

Having said this, Birchall’s book also becomes a bit tedious at points. While I enjoyed reading about the intrigue and various battles, the book often devolves into a mere litany of one fight after another. In an attempt to remain true to actual events, the author has chosen simply to recount the facts as he sees them, avoiding too much philosophizing or theorizing. But this is precisely what the raw material here could benefit from: a bit of authorial interpretation that would help those of us who did not live through all of this to step out of the particular events and better understand the broader issues. The focus is so much on events in the street that as a reader, I felt as if I was missing out on the bigger picture. Additionally, because of the focus on first-hand accounts from leftists, there is also a tendency for the book to make it sound like the anti-fascists always won the confrontations in which they engaged. The book, in fact, left me with the impression that the fascists were not really much of a threat at all, considering how often they seemed to cut and run. Unsurprisingly, if you look at sources that tell some of the same stories from the other side of the political divide (like the website for Blood and Honor), you get a completely different account of the winners and losers. I suspect that the real truth lies somewhere in between the extremes.

Another book, Mark Bray’s Antifa: The Anti-fascist Handbook, goes into great detail putting the movement into its historical and philosophical context. It still unapologetically champions the perspective of Antifa (and so, by the author’s own admission, it is far from an objective history), but Bray is more diligent in trying to define and articulate the purposes and aims of the movement rather than just chronicling street fights. Tracing anti-fascism back to the 1930’s, Bray’s book characterizes the current movement as a continuation of the struggle against European fascism, as well as the struggle against racist movements like the KKK here in the US.

Another book, Mark Bray’s Antifa: The Anti-fascist Handbook, goes into great detail putting the movement into its historical and philosophical context. It still unapologetically champions the perspective of Antifa (and so, by the author’s own admission, it is far from an objective history), but Bray is more diligent in trying to define and articulate the purposes and aims of the movement rather than just chronicling street fights. Tracing anti-fascism back to the 1930’s, Bray’s book characterizes the current movement as a continuation of the struggle against European fascism, as well as the struggle against racist movements like the KKK here in the US.

While acknowledging the difficultly of trying to sum up the ideals of a movement including anarchists, socialists and Marxists, Bray defines Antifa as, “an illiberal politics of social revolution applied to fighting the Far Right, not only literal fascists.” (p. xv) So, according to Bray, Antifa is not so much “anti-fascist” as it is anti-right wing. I confess that I found this a bit disappointing, as the simplicity of simply being against fascism, without any further agenda, was what first fascinated me about Antifa. Bray warns, however, that Antifa “should not be understood as a single issue movement. Instead, it is simply one of a number of manifestations of revolutionary socialist politics (broadly construed).” (p. xvi) Bray apparently doesn’t speak for some of the apolitical English soccer hooligans who (according to Birchall) joined anti-fascist street fights just for the thrill of it. The only agenda they seemed to have was punching Nazis in the face.

One of the most interesting parts of Bray’s book is Chapter Five, in which he responds to some of the most common criticisms of Antifa from liberals. Primary among these criticisms is that Antifa does not respect free speech; a charge that Bray claims is a red herring distracting attention from deeper, more substantial issues. He points out that the US Government already puts restrictions on free speech, and in times of crisis it is generally held by both conservatives and liberals that free speech can legitimately be restricted even further. The right to free speech, Bray suggests, is not a right without any constraints whatsoever. There are always exceptions to the rule, whether it be “obscenity, incitement to violence, copyright infringement, press censorship during wartime, or restrictions for the incarcerated.” (p.153) Thus, when liberals criticize Antifa in this way, their criticisms also apply to the very system that they do support. The difference between Antifa and mainstream liberals is that:

…liberals pretend that their limitations are apolitical, while anti-fascists embrace an avowedly political rejection of fascism. Anti-fascists reject the notion that politics can be reduced to the “neutral” management of disparate, atomized interests. They break through the liberal desire to confine the question to the realm of individual rights by foregrounding the ongoing collecyive struggle against fascism. When they say “never again,” they mean it, and they’re willing to use any means necessary to make sure. (pp 153-154)

In truth, the underlying intention behind the right to free speech in the first place is the promotion of diversity and freedom. In confronting those who want to use public speech in order to destroy diversity and freedom, Antifa is in fact fighting for something more fundamental and important than free speech itself. They are fighting to defend the social conditions under which free speech can actually continue to exist. The Nazis, on the other hand, want to use free speech in order to eventually destroy it.

Bray points out that there is, in fact, a wide diversity of opinion within the ranks of Antifa about the issue of freedom of speech. Some members of the movement claim that the right to free speech is one promised by the government. As opponents of the government, members of Antifa are thus not bound to such promises. Others argue that Antifa is not at all restricting fascist freedom of speech, but rather are targeting fascist organizing. Still others argue that they are indeed pro-free speech; but for everyone except fascists. Whatever the particular arguments are in this regard, Bray states it is generally the case that most of Antifa are not “free speech absolutists.” (p. 153) They do not regard free speech as an inalienable, sacred right.

This last point is what inspires some critics to charge that Antifa is itself a totalitarian movement, no better than the Nazis themselves. “Shutting down Nazis makes you no better than a Nazi!” (p. 162) I’m reminded of the lyrics from “Smash the Nazis,” a 1980’s song by Art: The Only Band in the World:

Bray defends Antifa against this charge with a simple and clever response: the worst thing about Nazis is not that they are intolerant to free speech. The worst thing about Nazis is that they promote “white supremacy, hetero-patriarchy, ultra-nationalism, authoritarianism, and genocide.” (p. 162) Equating Antifa with the Nazis on the basis of one shared attribute – indeed on one of their least relevant shared attributes – is spurious. It is like equating Buddhism with Nazism on the basis of their shared use of the swastika as a symbol; or equating Catholicism with Nazism on the basis that both promote group solidarity among members. As Bray writes, “If your main objection to Nazism is its suppression of the meetings of the opposition, then that says more about your politics than those you are critiquing.” (p. 162)

I’m still not sure that I fully understand the true nature of Antifa after reading either Birchall’s or Bray’s books. Neither work makes any pretense to being objective, and both rely predominately on accounts from advocates of the left in reconstructing their histories of the movement. As a result, both works, while claiming to tell the “real” story of anti-fascism, nonetheless are quite skewed and partisan. Thrilling as they are in their street-level perspectives, neither book presents anything like a clear-headed or dispassionate account. And while I am not unsympathetic to the claim that we shouldn’t be dispassionate in our attitudes toward fascism, I also am afraid that the more confident any group becomes that it alone is on the side of absolute Truth and Goodness while everyone else is on the side of falsehood and absolute evil, the more likely it is that atrocities might soon follow.

That being said, I do support the right of people to confront fascists (or any other assholes) in the streets. Personally, I think that when people go out in public and start making inflammatory statements – right, left or otherwise – they should be prepared to face the consequences. The free speech of those who are intent on intimidation is no more important than the free speech rights of those who seek to fight against intimidation. I think that when you start publicly insulting and intimidating others, you should expect that someone potentially might punch you in the nose.