File download is hosted on Megaupload

Today I need to put the final revising touches the article that I submitted a couple of months ago to the European Journal of Archaeology as part of a section on digital archaeology. You can read the original here.

One of the critiques of my paper is that the conclusion is a bit weak sauce (my language not theirs). In part, that’s by design. I don’t want to dictate how people use digital tools in their archaeological practice. The issues are complex and projects, pressures, and perspectives are diverse.

On the other hand, I do want archaeologists to think about how digital tools change the relationship between the local and the global, the individual and assemblage, and archaeological work and efficiency. I’m not sure that I communicate this very well in the conclusion, but here’s what I say:

Conclusions

Ellul and Illich saw the technological revolution of the 20th century as fundamentally disruptive to the creative instincts and autonomy of individuals because it falsely privileged speed and efficiency as the foundations for a better world. The development of archaeology largely followed the trajectory of technological developments in industry and continue to shape archaeological practice in the digital era. Transhuman practices in archaeology reflect both long-standing modes of organizing archaeological work according to progressive technological and industrial principles. The posthuman critique of transhumanism unpacks how we understand the transition from the enclosed space of craft and industrial practices to the more fluid and viscous space of logistics. In short, it expands the mid-century humanism of Ellul and Illich offers a cautionary perspective for 21st century archaeology as it comes to terms with the growing influence of logistics as the dominant paradigm of organizing behaviour, capital, and knowledge.

An “archaeology of care” takes cues from Illich and Ellul in considering how interaction between tools, individuals, practices, and methods shaped our discipline in both intentional and unintentional ways. If the industrial logic of the assembly line represented the ghost in the machine of 20th century archaeological practices, then logistics may well haunt archaeology in the digital age. Dividuated specialists fragment data so that it can be rearranged and redeployed globally for an increasingly seamless system designed to allow for the construction of new diachronic, transregional, and multifunctional assemblages. Each generation of digital tools allow us to shatter the integrity of the site, the link between the individual, work, and knowledge, and to redefine organization of archaeological knowledge making. These critiques, of course, are not restricted to archaeological work. Gary Hall has recognized a similar trend in higher education which he called “uberfication.” In Hall’s dystopian view of the near future of the university, data would map the most efficient connections between the skills of the individual instructors and needs of individual students at scale (Hall 2016). Like in archaeology, the analysis of this data, on the one hand, allows us to find efficient relationships across complex systems. On the other hand, uberfication produces granular network of needs and services that splinters the holistic experience of the university, integrity of departments and disciplines, and college campuses as distinctive places. This organization of practice influences the behaviour of agents to satisfy the various needs across the entire network. The data, in this arrangement, is not passive, but an active participant in the producing a viable assemblage.

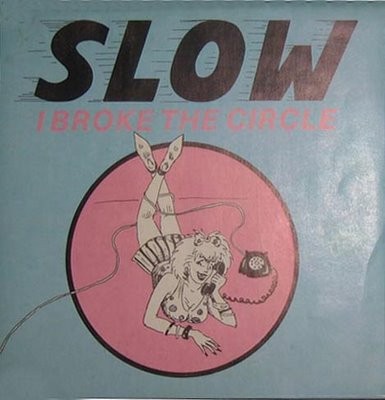

Punk archaeology looked to improvised performative, do-it-yourself, and ad hoc practices in archaeological fieldwork as a space of resistance against methodologies shaped by the formal affordance of tools. Slow archaeology despite its grounding in privilege, challenges the expectations of technological efficiency and the tendency of tools not only to shape the knowledge that we make, but also the organization of work and our discipline. The awareness that tools shape the organization of work, the limits to the local, and the place of the individual in our disciple is fundamental for the establishment of an “archaeology of care“ that recognizes the human consequences of our technology, our methods, and the pasts that they create.