File download is hosted on Megaupload

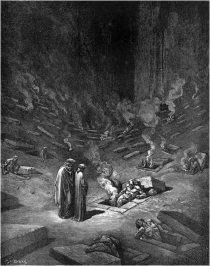

Once again we find our friends Dante and Virgil in the dismal gloom of Hell, bedraggled as they are on their pitiless journey into the Underworld, with each passing vignette of misery and torment they face naturally becoming more and more difficult to behold. Now in the Sixth Circle of Hell, our pair find themselves amongst the Heretics – sinners who, in the estimation of the Roman Catholic Church (RCC), espoused beliefs that were somehow at odds with Vatican teachings. A Heretic is distinct from a Pagan, mind you, for pagans are simply unaware that their belief system is sinful, presumably waiting to be ’saved’ by the foot-soldiers of the Christian God. Pagans, such as Virgil, Aristotle, Plato, Buddhists, Confucianists, Hindus, and anyone else who wasn’t a Jew or a Muslim – had different belief structures simply because they had not yet been shown the light of the Lord. Heretics, on the other hand, had heard the gospel – literally good news in Old English – and perhaps had even been baptized into the kingdom of Christ, yet still chose a different path.

Dante discovers that the Heretics are condemned to an eternity trapped in flaming tombs or coffins – presumably a reference to the auto-da-fé (burning at the stake; literally act of faith in Portuguese) that heretics received at the behest of the Pope during the Spanish Inquisition. The Heretics also suffer an additional torment: the only knowledge they have of the world is that of the future. They have full knowledge of the future and are powerless to stop it from unfolding.

One such heretic that Dante chances upon is Epicurus, an Ancient Greek (and therefore really more of a pagan than a heretic) philosopher who believed that – get this – all matter was composed of individual and indivisible components called atoms, after the pioneering work of his predecessor, Democritus. Interestingly, Epicurus’s more fervent writings on the enjoyment of life give us the term epicure, which today signifies someone who is really into food and wine…Padma Lakshmi, or Anthony Bourdain, for example.

One such heretic that Dante chances upon is Epicurus, an Ancient Greek (and therefore really more of a pagan than a heretic) philosopher who believed that – get this – all matter was composed of individual and indivisible components called atoms, after the pioneering work of his predecessor, Democritus. Interestingly, Epicurus’s more fervent writings on the enjoyment of life give us the term epicure, which today signifies someone who is really into food and wine…Padma Lakshmi, or Anthony Bourdain, for example.

All fine and good. But Epicurus also peddled in the business of denying the existence of the Gods — or a singular God — or any God, really, opting instead for rationality, empirical analysis, and complete enjoyment of the world around him.

Had Epicurus lived during Dante’s time, he too would have been burned at the stake.

And yet, today Epicurus’s notions seem somewhat tame, fortunate as we are to live on the better side of the Age of Enlightenment. Though technically paganish by all accounts, Epicurus’s writings survived the Axial Age, thrived during the Roman empire, even finding their way into the ruins of Pompeii, and lasting well into the age of Christendom. Indeed, for centuries into the Middle Ages, Epicureans, as they were called, enjoyed the uninhibited practice of their hedonist worldview, drinking, dancing, and fucking their way into the absolute nothingness of material decay that each of us must resign ourselves to, according to most well-respected, modern-day physicists.

Their cemetery have upon this side/With Epicurus all his followers,/Who with the body mortal make the soul.

Much to the chagrin of the RCC, Epicureans took their namesake’s lead in regard to his atomic materialism, believing that the ‘soul’ was a material, not a spiritual, phenomenon. They believed that, rather than escaping to an afterlife, the soul died with the body. The goal of the Epicureans was, in a very rational, Greek sort of way, to achieve ataraxia – a kind of timeless nirvana, where one felt no fear of death nor the uncertainty of the future.

This being their soulless, godless view of the universe, the Epicureans went even further in their philosophy. Like more thoughtful, more respected disciples of Ayn Rand, the Epicureans believed that pleasure in life was the ultimate goal of the individual, and they were often confused with outright hedonists, though the truth is far more obscure (and obscene): the Epicureans were like scientific bon vivants, the Richard Feinmans and Neil Degrasse Tysons of their day. And for centuries of Catholicism, Epicureanism was essentially the foundation of Western-derived heresy, which neatly explains why Epicurus became of one the RCC’s most be-loathed bête noires, eventually garnering him a place here in the Sixth Circle as opposed to the more demure Limbo.

But were Epicurus’ teachings really all that incompatible with those of Jesus of Nazareth? Furthermore, why shouldn’t an ever-present urge to pleasure ourselves find purchase in our hearts and minds alongside the good news of the Lord? Is Satan truly to blame for our incredulity of a higher power, or is there something more concrete we could turn to and blame?

Well, long before the founding of Christianity, the human world struggled with this very uncertain relationship between the body, the mind, the soul, and the heavens. Consider the Egyptians, whose obsession with death consumed their lives, and who rendered the body and the soul as two separate aspects of the same, entire physical being. The ancient Egyptians, consummate pagans that they were, ushered in the “notion of a material soul – an entity that the embalmed mummy did not represent or symbolize…but simply was.” (from The Secret Life of Puppets)

To these master builders, sculptures, and embalmers, there was no separation between the body and the soul (unlike what we in the post-Descartes world generally adhere and refer to as dualism). In their worldview, if you built a statue of the Pharaoh, it was the Pharaoh. But it also worked in the opposite direction, as they “believed that the physical body of a human or animal could, with human intervention, become an immortal divine body.” (ibid)

As those pesky and overly cerebral Greeks began to intermingle with the ancient Egyptians, concepts of the mind/soul relationship began to change. Like us, the Greeks had something of a theological dualism at play, but it was founded on the principles of the ideal. To them, all forms found in nature, including the human body and mind, were “mere shadow[s] of the divine model.” Our bodies and souls were intrinsically related, but the former was more like a shade of the latter, which existed on a different, more abstract plane.

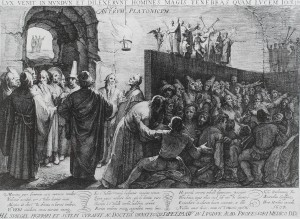

Consider Plato’s Republic, widely considered the foundation of all western philosophy and thought:

Behold! Human beings living in a underground den, which has a mouth open towards the light and reaching all along the den; here they have been from their childhood, and have their legs and necks chained so that they cannot move, and can only see before them, being prevented by the chains from turning round their heads. Above and behind them a fire is blazing at a distance, and between the fire and the prisoners there is a raised way; and you will see, if you look, a low wall built along the way, like the screen which marionette players have in front of them, over which they show the puppets.

Having set a rather gloomy stage thus, good Plato provides the kicker:

“[T]hey see only their own shadows, or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave…”

This “Allegory of the Cave” expertly demonstrates the Greek conception of that crucial separation of the perceived world from true, abstract reality. It wasn’t until Plato came along and dropped this on us that Western humans began to formally see that the soul itself was perhaps an abstract thing. Each of those held captive in the Cave only knew of themselves by virtue of their own shadow. Their true essences existed in the divine World of Forms, along with all the other puppets.

Likewise, it was Plato who later sealed the deal in regards to dualism with his Timaeus, wherein he inaugurated the concept of the demiurge, or public worker: i.e. the entity who is responsible for having created the visible, physical, world. From then on, as the demiurge sunk it’s way into Western thought, we gravitated towards this concept of ‘God’ as a higher power, existing somewhere beyond us.

Therefore, if one were to stick Plato and Epicurus into a metaphorical boxing ring, Plato would surely beat the fuck out of Epicurus. But wouldn’t it also be truthful to say that Epicurus would likely throw the match, sneak out the back door with his heresies intact, only to emerge centuries later in the guise of physics and cosmology? And therefore the world is no more settled in regards to the teachings of the RCC and the ‘heresy’ of modern physics than it was in Dante’s day. How best to tackle this conflict in the realm of music?

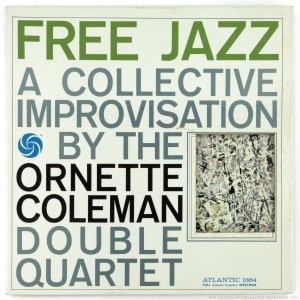

Ornette Coleman – Free Jazz: A Collective Jazz Improvisation (1961)

Ornette Coleman – Free Jazz: A Collective Jazz Improvisation (1961)

My entrée to jazz began with the seminal jazz works of the Sixties and Seventies. In other words, I had bowed to the pressure of album re-release fervor and put the cart before the horse. But thus having satisfied my initial hunger for jazz, I began a long progression backwards, trying to find the source of it all. And much like dragging a giant rope found laying about the ground, closer and closer towards me, deeper and deeper from the darkness, I dragged along with it some not-so-subtle relics of the past.

It was in like manner that I discovered Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation by avant garde jazz composer Ornette Coleman. More a two-part improvisational explosion set to vinyl than an actual album, Free Jazz inaugurated an entire sea change in jazz. The title itself became the moniker for a burgeoning movement, signified by excessive instrumentation, wide-open phrasing, and the eschewing of the typical melody/solo/melody structure of previous forms.

I was 20 or 21, and I had already heard Coltrane’s Ascension, Eric Dolphy’s Live at the Five Spot, Pharoah Sanders’ Thembi and Live at the Village Vanguard Again! (as sideman to Coltrane), Archie Sheep on New Thing at Newport (half and half with Coltrane), and Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew (no Coltrane: he was dead…); and then I heard Free Jazz, and I suddenly got it. I understood implicitly, within the first four measures of Coleman’s dizzying masterpiece, where this vibrant direction in Western music had come from. Despite the difficult nature of this music, the feeling I had upon hearing it was an incredible affirmation of everything I had already been hearing.

At the time of its release, Free Jazz was unlike any other music in existence, though it certainly had parallels in other cultural forms. Consider the cover art of the original release of Free Jazz, a simple reproduction of “White Light” by painter Jackson Pollock – rather telling as the AbEx and Free Jazz movements had sisterly relationships in the minds of their creators.

Similar to the many emblematic works of the AbEx movement, initial reception of Coleman’s masterpiece was less than stellar. Consider the review of Free Jazz by Down Beat magazine’s John A. Tynan, who wrote, “If nothing else, this witch’s brew is the logical end product of a bankrupt philosophy of ultra individualism [sic] in music.”

Though Tynan’s panning has long since been overshadowed by lavish praise for Coleman’s entire catalog, do notice how his critique hinges on individualism, as if a higher power is being denied credit for producing beauty in the world. He goes on to say:

‘Collective improvisation’? Nonsense. The only semblance of collectivity lies in the fact that these eight nihilists were collected together in one studio at one time and with one common cause: to destroy the music that gave them birth.

Perhaps what Tynan meant by “destroying the music,” was that Coleman was trying to destroy the established rules of music. In the context of mid-century jazz, we can forgive Tynan for seeing this as outright heresy. But unlike the dogmatic world of Catholicism, non-traditional thinking is truly the lifeblood of creative genres and avant garde movements throughout cultural history: per Marx and Engels, with the destruction of old rules and old forms, we dialect new rules and new forms. As Tynan wrote, “Rules? Forget ’em.”

Have no fear, Mssr. Tynan. They’re forgotten!

Thankfully views such as Tynan’s were clearly in the minority, and as I mentioned, they were representative of a typical post-war, conservative and traditionalist view of jazz. Whether it was, as Tynan claims, pure self-indulgence or utter genius, Free Jazz was a masterpiece of free thought and expression, and clearly meant something wondrous to the cold isles misfits who inundated the ranks of jazz fans, and propelled along the Sixties to its logical extreme: freedom from fear, freedom from reason, and pure knowing.

As Coleman himself asked in his own Down Beat op-ed,

…why don’t we Americans, who have a duty to our neighbor and our mother country, get off this war-jazz, race-jazz, poverty-jazz and b.s. and let the country truly become what it is known as (GOD country)—unless we fear God has left and we must make everyone pay for His leaving? I am sure if we prayed, He’d at least give the place back to the Indians because it isn’t going to mean anything to us anymore if we find that we are hating each other.

Maybe God will let us all go back home.

A bit rambling, to be sure. But also rather forward thinking, wouldn’t you agree? For now it seems inevitable that less than a century after receiving the conveniences of the post-atomic age – frozen dinners, devastating military infrastructure, birth control, diet soda – we would find ourselves here in the teenage gloom of the twenty first century, beset with an inexorable urge to rid ourselves of it all, purposely reverting to simpler versions of our apparent selves. Indeed, those of us who do not eschew the convenience of the coming Singularity by donning the vestiges of Williamsburg and Portland counter-culture are labeled as heretics.

But even the post-modern, hipster contingent of our culture can be shorn bare in this same light: this coveted demographic that shrugs off electricity, razors, toothbrushes; that adores twee, accordion-driven music played by men and women in fin de siècle vestments; these twenty-somethings who pray to the alter of ‘maker culture’ with a strange, unearned bravado – one that manifests itself in the urge to pickle things, wear scarves, cardigans, suspenders, use actual film, ride fixed-gear bikes; one that reels at the possibilities of the next start-up company, innovation incubator, or pop-up arts event. With any hope, this urgency will one day evolve into the same kind of soulless spending power that is killing the lot of us.

With this in mind, who could possibly make sense out of the term “going forward?” What does that even mean in the here and now?

But I suppose this same question haunted every generation sitting in the crux of a social whirlpool, closing in on itself, devouring itself, like our galaxy; like every galaxy. This same uncertainty of the future, though present in all humans, must surely be greatest in those that witness not social unrest, war, or injustice, but those possessing a subsequent complacency in regard to these things; not a peaked interest in the amazing, inspiring acts of beauty or creation, but rather a prosaic indifference to them.

Perhaps that is why people initially hated on Ornette Coleman: fear of the future… the only thing the Heretics in Dante’s Sixth Circle can know of the world. We’re at what AdBusters magazine calls the Dead End of Western Civilization. Those who recognize it and attempt to stop it are regarded as the folks who try to prevent a hungry mob of lost hikers – grown mad from their own starvation – from eating one another.

Then, as now, Coleman’s views on the industry – and the musical form he gave birth too – were seen as heretical, nihilist, self-indulgent, and rather crude. Fortunately for us, he was not alone, for he was joined by the likes of Eric Dolphy, Archie Schepp, John Coltrane, Pharaoh Sanders, Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, and many others, who would eventually finish out the decade strong.

As I mentioned above, one crucial thing Dante learns while speaking to various heretics, as they flit about in their burning caskets, is that the only thing they know of the world of the living is the future. Their unique form of damnation it seems is an eternity knowing and understanding what awaits the living on Earth.

Perhaps that was Coleman’s punishment as well, for, in Pete Welding’s Down Beat review of this same album (published alongside Tynan’s, mentioned above), he makes clear that, “using only the sketchiest of outlines to guide them, the players have fashioned a forceful, impassioned work that might stand as the ultimate manifesto of the new wave of young jazz ex-pressionists [sic]. The results are never dull…”

Having assembled for this collective improvisation a rather astounding cavalcade of jazz greats – including, but not limited to, Don Cherry, Billy Higgins, Freddie Hubbard, Charie Haden and Eric Dolphy – Coleman waltzed them all into A&R Studios and subsequently gave them very few directions other than a soloing order and sparse prompts for the occasional transition to a new phrase. The result, although not unlike a long history of big band improvisations à la Dixieland jazz, was nonetheless controversial, complex, and revolutionary.

Later releases and remasters of the original aside, this record only officially has one track on it, “Free Jazz”. Its importance in the world of jazz is difficult to overstate, as it lent its name to an entire genre of jazz that was just forming near the end of the late Fifties, and also stands as the first album length improvisation of any kind or any genre.

Stereo Production and the Double Quartet

Stereo Production and the Double Quartet

Free Jazz is really just the free soloing of two separate standard jazz quartets, playing simultaneously, one in each ear of the listener. Thus did Coleman insist on employing newly minted stereo production techniques to separate out one quartet in each of the two channels of the stereo field. Mind you, at the time this record was conceived and subsequently produced, stereophonic recording and record production was only three years old, as far as its use in the music industry was concerned. Just to give you some perspective, the first iPod was released a full eight years after the initial release of the MP3 specification. It’s an understatement, therefore, to say that the stereo soundstage was, in and of itself, avant garde territory, especially when utilized as part of the production and delivery itself.

The effect on the first time listener is nothing short of revelatory, after which there is no going back. The above description may sound blasé to us now, but one must appreciate how truly weird this album must have sounded as the country was ramping up from the sedentary days of Eisenhower to the brave new world that Kennedy was promising, buoyed as it was by the Space Race, yet bogged down by the then-nascent Cold War, The Bay of Pigs, the Freedom Riders, the construction of the Berlin Wall, and the laying of groundwork for the coming war in French IndoChina.

But like all forms of culture, there is no accounting for taste. We each have our own likes and dislikes, and these too are mutable, evolving through our life. While that’s certainly true, I still remember the instant I first turned Free Jazz on, sitting in my car with snow tumbling down outside. I adored it and its unassailable expression, and because of that instant, Free Jazz will always exist there in the abstract world of forms, there in the diffident exigencies of the heart, there in the nondescript velvet of the universe’s corner pocket, and there in nestled corpuscles, given way to that place where all our hands entwine. There like light, destined to travel into our eyes, or be absorbed into the rich darkness of forever.

Ornette Coleman, the ultimate jazz heretic, sadly passed away a few days before I began writing this piece. But his soul lives on in his music, in the abstract, in the atoms of peace and vibration, burning softly in the afterworld, and in all notes known to the Universe.

R.I.P. Ornette