File download is hosted on Megaupload

On Friday afternoon, after a long week filled with jet lag, frantic course preparation, and seemingly endless page proofs, I snuck off to hear UND’s music department perform their regular faculty showcase. I was particularly excited to hear Mike Wittgraf’s “Hearing Corwin Hall” performed. This piece developed from our work at the Wesley College Documentation Project which focused on studying the four buildings on UND’s campus associated with Wesley College prior to their demolition in May 2018.

Last week, this piece debuted at the KYMA International Sound Symposium (KISS) in Santa Cruz earlier this month and this was the first time that it was performed in North Dakota.

Here’s Mike Wittgraf’s abstract for the piece:

Hearing Corwin Hall uses sound sources from the third floor of two adjoining now-demolished buildings, resulting in a radical altering of the acoustic space of that location since the time of recording. It is fascinating to look up at the open space where the third floor used to be, twenty feet above the ground, and imagine the former building structure and its acoustic signature, as well as the mics, cables, and people present during the recording. Corwin and Larimore Halls, formerly on the campus of the University of North Dakota, demolished in May of 2018, were originally constructed in 1909 as part of the Methodist-Church-affiliated Wesley College, which later was absorbed by UND. For a period of time Corwin Hall housed the Music Department, and adjoining Larimore hall served as a women’s dormitory. Hearing Corwin Hall uses source sounds from a recording taken on March 13, 2018, after the buildings were abandoned, but before they were demolished. The recording took place on the third floor, which included the Corwin recital hall. Eight microphones were placed in a variety of locations. During the recording the composer presented an informal “memorial service” that included a keyboard synthesizer performance of five hymns from the Methodist hymnal, after which attendees were encouraged to wander the third floor and engage with the microphones in order to capture the acoustics of the space. Hearing Corwin Hall takes digital data from these sound sources and applies them to time-based parameters in a live-processing environment in order to symbolize the fleeting nature of time and objects, as well as highlight the acoustic signature of the space. Using time in this manner creates an altered state in contradiction to the usual passing of time. Video projection of historical and recent photos, as well as photos of the demolition and post-existence of the buildings accompany the music.

~

Our plan is for Mike to perform it once more on campus and to record it for publication. My hope is to have something suitable to publishing in Epoiesen over the next six months. Our article will have three themes to it (as I conceive of it not) which work at the intersection of archaeo-acoustics, the study of time, and the considerations of how we experience the recent past especially after it has been radically altered.

1. How Buildings Sound. Over the past few years, my friend Amy Papalexandrou and I have been talking about the acoustics of Byzantine churches (and she’s published on this here and Sharon Gerstel here). As Amy makes clear, sound plays a key role in how we experience our environment and it was particularly significant in the context of monumental ritual spaces in the Byzantine and post-Byzantine worlds. The location of particular features in Byzantine churches, the movement of individuals in the spaces, and the intentional and unintentional effects on the sound of ritual in these buildings contributed to how individuals experienced the rituals there.

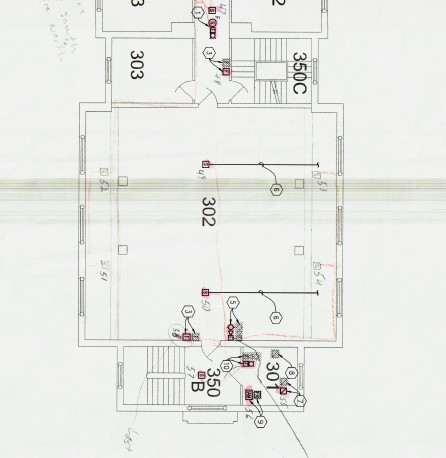

For Corwin Hall, like the nave of a Byzantine, this has particular significance because the room where we performed the recording was a recital hall for the music department of Wesley College. The space featured a deliberate design with a proscenium arch, acoustic shell, and vaulted ceilings which gave the room particularly desirable acoustic characteristics. By arranging eight microphones throughout the building, including in key spaces in the recital hall, we were able to capture the sound of Mike Wittgraf’s performance of a series of hymns from the Weslyean hymnal as well as the ambient sounds of a group of people moving throughout the space. It makes sense to document the space a recital hall with sensitivity toward its acoustics just as archaeologists have long studied lines of sight in ancient buildings or traces of movement between rooms.

2. Time. Our work to document the sound of Corwin Hall, however, was an effort to capture the original sound of the room or the building. The room itself endured a series of significant modifications that included a solid wall with a single door along its north side that separated the recital hall’s acoustic shell from the rest of the room at the proscenium arch. Moreover, air-conditioning ducts were installed around the room’s perimeter and covered in acoustic tile. The windows lacked curtains when we recorded and the room was filled with discarded desks and other furniture removed from the rest of the building. In other words, the room as it was preserved was rather different from its original design. That being said, the original design persisted, even in its compromised state, and, as a result, our recording was a kind of state plan which showed the existing state of the space while also indicating its original arrangement.

Archaeologists regularly use photography and illustration to accomplish this kind of time shifting. We indicate earlier phases of a building through the visual inspection of existing structures and combine the past and present states of a building or object in a plan. To accomplish this kind of acoustic time bending we also placed microphones (some of which seem to have worked… ) in both Corwin Hall and Larimore Hall to which the former recital hall was attached through the doorway in its northern wall. This door merged the spaces of the recital hall with the offices carved out of rooms in the former women’s dormitory and transformed its acoustic signature. This created new spaces to record and hear the sound of the recital hall and allowed us to record the sounds of the recital hall in a way consistent with its later use as a classroom and offices. Individuals were encouraged to move and interact with the microphones so that we could record the sound of people through the space from various locations. In effect, we were able to create an acoustic phase plan that, however imperfectly, captures both the original plan and the state plan.

I’ve recent come to appreciate how our time in Corwin Hall both during the recording and during the larger research project served as what Sara Perry has called “bodystorming” as we discussed with Mike, the research team, and members of the public the history, space, and sound of the building. Our microphones captured our movement through this space and superimposed our research project, public engagement, and performance.

3. Presenting Corwin Hall. Mike’s performance of “Hearing Corwin Hall,” however, was not a literal presentation of the sound of the space neatly arranged for the audience’s consideration. Mike’s piece sought to bring the audience not only into Corwin Hall as a space but into the experience of Corwin Hall as the site of a research project, as an example of change on campus, and in the process of being transformed from a standing building to well manicured lawn that preserves beneath the surface archaeological remains of the former college. To do this, Mike integrated sound, video, and performance(s) in “Hearing Corwin Hall” in distinctly evocative ways.

Last week, I heard an interesting paper by Ruth Tringham (the first paper here) on the use of sound to evoke emotional (and intellectual) responses from archaeological sites and objects. A key point that Tringham makes is that archaeologists have been too dependent on texts (both written and spoken) to communicate the past. She considers the work of the composer György Ligeti who has used singers to create emotional states without the use of text and calls attention to Alice Waterson’s work “Digital Dwelling” (or here) on the Neolithic village of Skara Brea in Scotland which similarly uses video and audio, but not text, to communicate the experience of both the space and the past.

Mike’s piece integrates both the acoustic space of Corwin Hall with its final months and a number of related performances designed to recognize the importance of these places on UND’s campus and in the community. For example, both the video, the sounds, and Mike’s performance communicate the violence of the building’s demolition both physically and emotionally. The destruction of these buildings embody an ongoing conflict on campus between an administration who is eager for rapid economic, cultural, and physical transformation across campus and faculty and community members who remain committed to established practices and priorities. The violence of the piece (and its performance) captures how the destruction of these buildings – their transformation from classrooms and offices into archaeological remains – generated significant emotion across campus and in the community.

What makes this piece even more unique is that Mike integrates our efforts to document and commemorate the building into his performance. My voice, for example, is merged with the acoustic signature of Corwin Hall and looped over and over so that the words have become unintelligible, but it nevertheless evokes the sound of a bustling campus building. Sheila Liming’s bagpipes, played during a campus ceremony to honor Harold Holden Sayre after whom one of the Wesley College buildings was named, likewise loop through the performance as the tension and anxiety builds. My voice reflects the campus din as well as the work of documenting the Wesley College. Sheila’s bagpipes communicates both the death of these buildings as visible monument as well as how we commemorated their memory. The blurring our experience of the buildings between their lives as active campus structures and as objects of abandonment, study, and commemoration.

More importantly, “Hearing Corwin Hall” communicated the violent tension between destruction and commemoration, between standing buildings and archaeological remains, between tradition and progress, through the linearity of texts, but through sound. This does not make the piece any less archaeological, however. It remains dense, nuanced, complex, rhythmic, and multivocal.

I can’t wait to share it with a wider audience.